Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta. (1) Courtesy 'The Centre for the Study of the Life and Work of William Carey D.D., 1761 - 1834.' Joshua Marshman's plan for the extension of education was introduced to public notice in 1816 with a little pamphlet called 'Hints relative to native schools, together with the outline of an institution for their extension and management'. It succeeded beyond their most sanguine expectations. Contributions poured in with a degree of liberality which marked the confidence the missionaries enjoyed in Indian society. Within 12 months schools were established in a circle of about 20 miles round Serampore, at the earnest request of the inhabitants. 45 were opened and 2,000 children received the elements of knowledge in their own language.

At the close of the year the missionaries drew up a report embracing the years since 1815. They stated that the number of adults baptised amounted to 420, raising the whole number to considerably over 1,000. The sacred Scriptures had been brought into circulation, in some cases in single gospels, in 16 of the languages and dialects of India. Regarding tracts, they observed, the number printed and distributed in the year 1817 amounted to a 100,000. In the 3 years embraced by the review, the number was 300,000, in 20 different languages.

William Ward's health began to decline under the influence of the climate and the pressure of his incessant labours, and he was advised to take a trip on the river for a change of air at the beginning of 1818. He proceeded to Chittagong where the church had been left in a destitute condition after the sudden death of Mr. Debruyn. On his arrival he was surprised by the unexpected appearance of Felix Carey, of whom no tidings had been received for many months. He had been wandering for more than a year among the wild tribes on the eastern frontier of Bengal and had endeavoured to penetrate almost to the borders of China. He had been led to this romantic expedition by a desire to investigate the habits, language and religion of these unknown regions.

Ward persuaded him to return to Serampore, and Carey and Marshman were happy to welcome him back. He was engaged as his father's assistant and devoted his oriental acquirements to the translation of the Scriptures. Ward continued with his journey and visited Cox's Bazaar where he baptised 7 candidates.

On his way back to Serampore Ward visited an indigo factory at Nuddea. (2) A brief extract from his correspondence will serve to exhibit the tone of his feelings at the time.

'Yesterday morning at five, when I went to walk on the deck, the scene was truly exhilarating to my jaded spirits, so unused to new scenery and to a breeze on the river at such an early hour. The heathen were certainly right when they maintained that real happiness must be united to inward and outward tranquillity. A healthful body, the serenity of nature, flowing rivers, singing birds, and a soul all tranquillity contemplating infinite excellence, eternal realities, and boundless prospects, make up the blessedness of a Christian... I have been thinking of looking out for some spot for my future retirement, where I may erect a bungalow and have a Christian village, and devote my remaining days to the instruction of enquirers and the formation of young Hindoos for the ministry. It must be by the side of one of these lakes. I do not know what destiny may await me, but I do contemplate something of this kind, if I can but see a comfortable settlement of things at Serampore, and I see nothing now so desirable as such a mode for closing life. Yet, perhaps, my days are already closed, and these bilious attacks may soon liberate me from all further service in this lower world. I have not, however, any cause of regret, as long as I have strength to get through my labour, if all may be secured to God for thirty or forty years more. Yea, if I could be certain that Serampore would act with vigour in the cause for this time to come, I should be content to die, but my fears are strong for the future.' (3)

The Serampore missionaries, Joshua Marshman in particular, had for some time contemplated the publication of a newspaper in the Bengali language. The government of India had always regarded the periodical press with a spirit of jealousy, and it was then under a rigid censorship. It did not appear likely that a native journal would be suffered to appear and they hesitated long before they made any demonstration of their design. They resolved at length to feel the pulse of the public authorities by the tentative publication of a monthly magazine.

The magazine was called 'Dig-dursun' (5) and the first number contained an account of the discovery of America, the geographical limits of Hindustan, the chief articles of trade in India, Mr Sadleirs's aerial journey from Dublin to Holyhead, and a brief memoir of Raja Krishnu-chunder-roy, the renowned zemindar of Nuddea. In the last page were some brief notices of current events in the form of a newsletter. Copies were sent to the most influential members of government. It not only excited no alarm, but was received with unexpected approbation.

Emboldened by the lack of censure, and the public encouragement of the wealthy natives, Marshman and Ward determined to advance at once to the object in view, and issued a prospectus for the publication of a weekly newspaper in Bengali. The advertisement that announced this journal appeared in all the English papers for a fortnight, and passed under the eye of the censor. The missionaries expected day by day a notification to desist from the undertaking, but no such communication arrived.

On 31st May, 1818, the first newspaper printed in any oriental language was issued from the Serampore Press. It was called the 'Sumachar Durpun', or the 'Mirror of News'. Carey, who had passed 24 years under a suspicious and despotic government, regarded the publication with alarm. When the proof sheet of the journal was brought for final revision, on Friday evening, at the missionary's weekly meeting, Carey again urged his objection to the newspaper, and his fears of the result. Marshman assured him that a copy of it would be sent the next morning to the Chief Secretary, with an English translation of the schedule of contents, and that if any disapprobriation was expressed, the journal would be at once relinquished. No objection was manifested by members of the Council Board and 'Sumachar Durpun' was firmly established.

The novelty of a weekly journal gave the 'Durpun' great popularity among the natives of Calcutta, and the subscription list was headed by Dwarkenath Tagore. The influence of the journal, however, was confined to the metropolis.

The postage on newspapers was so heavy that a low priced paper like 'Durpun' had no chance of circulation in the interior of the country. Marshman immediately sent Lord Hastings a copy and requested some relaxation of the postage tariff. In his reply, Lord Hastings said that 'the effect of such a paper must be extensively and importantly useful. But to furnish such a prospect, extraordinary precaution must be used not to give the natives cause for suspicion that the paper had not been devised as an engine for undermining their religious opinions.' Marshman replied that their object was the general illumination of the country, and as it could not live without the patronage of the natives. This circumstance afforded sufficient guarantee that it would not be rendered offensive to their religious beliefs. In the course of a week Lord Hastings persuaded his colleagues on the Council to reduce the postage on 'Durpun' to one-fourth the usual charge.

In April 1818, the missionaries commenced an English monthly magazine to which Marshman gave the title 'Friend of India'. A name which was associated with Serampore throughout India in the 19th century, and was eventually to be the parent of the modern, Calcutta based, Indian national daily newspaper, called 'The Statesman'. Both the 'Durpun', and the 'Friend' were commenced while the censorship of the press was in full vigour.

The principle of the mission Carey embarked on in 1793, and his two colleagues in 1799, was that they should receive support from the Society until they were able to support themselves. Hence the Serampore missionaries relinquished all aid from England as soon as they had acquired independent means of subsistence.

After the the transmission of the letter of 15th September, in which the Serampore missionaries repudiated the demands of the Society, the junior missionaries in Calcutta formed a Union, on the principle of subordination to the Society, which Carey and his colleagues were said to have unwarrantably relinquished. The basis on which the Serampore mission was founded was the entire consecration of the proceeds of all labour to the cause of missions. The principle of the Calcutta Union was the surrender of the right over its income to the Society, for missionary objects.

The principle was distinctly explained in a document drawn up in 1818: 'The principles of the mission had always appeared to them to be that, on the one hand, all the moneys acquired by the missionary brethren in the service of the Society, and especially all permanent property, should be considered as belonging to the Society, and as subject to the final control of the Committee in England; and that, on the other hand, the Society should supply the wants of the missionaries during their lifetime, and should make a provision for their widows and orphans.'

The Serampore missionaries had relinquished all aid from England while the missionaries in Calcutta continued to draw their salaries, to the extent of £1,000 a year, long after they succeeded in obtaining an independent income.

After a short residence at Serampore, Mr. William H. Pearce was invited to join the Calcutta missionaries as the result of their own choice, and not as the nominee of the Society. But he considered himself bound to the Society, under whose auspices he had come out to India, and he declined to accept the offer till he could communicate with the Committee. Before their reply reached him he removed to Calcutta and joined the Junior Brethren.

The Calcutta Union was soon strengthened by the arrival of Mr. Adam. He had recently arrived as a missionary in India, and on quitting Serampore, where he had been a temporary resident, he addressed a valedictory letter to the missionaries containing severe reflections on Joshua Marshman. Carey and Ward united in replying to it and pronounced these aspersions to be unfounded and calumnious.

The establishment of a Calcutta mission on the Serampore model Towards the close of the year 1818, the missionaries in Calcutta retired from the church over which Carey and his colleagues presided and formed a separate church and congregation. They formed an establishment on the model of Serampore, opening boarding schools for children of both sexes, and set up a press and type foundry. From some of the other missionaries of the Society, Carey and his associates were visited with the severest anathemas, and they were advised by one of them to appoint a day of humiliation for their transgressions.

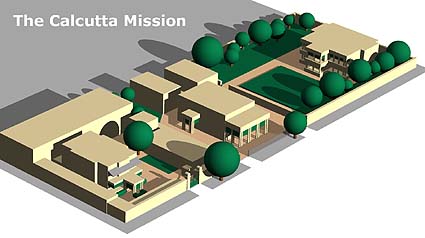

Left to right: Baptist Mission Press; the Baptist Chapel with the Manse and Church Hall behind; the Field Secretary's house.

(1) In this 19th century engraving, the gate is exactly as it was in the1960's (without the sign). The building you see through the gate was known as the flats. In the 1950's the superintendent lived on the top right, the assistant superintendent, bottom right (the two windows on the bottom right were our sitting room). The manager of the machine department lived on the top left, the bottom left was for visitors and was mostly unoccupied as it had little natural daylight and was within feet of the foundry. The colonnaded entrance portico (which also housed a fish tank), is just visible. The only two differences to the 1960's Press, that I knew, were that: a) verandahs were added to the front of all the flats, and b) what looks like a wooden covering over the portico was not there. The rustication on the ground floor I recognise. The flats were built about 5 feet off the ground to allow for flooding in the monsoon. The offices and composing room were behind the flats, and the machine department was to the right. Horse drawn vehicles (known as a horse-garries), such as the one seen through the gate, were still used for delivering goods to the customer in the 1960's (see BMP on the Miscellaneous Page). This one looks as if it is carrying people as it is leaving the entrance to the flats. According to Ward, Pearce's preferred form of transport was a gig, a light two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. According verbal tradition, passed on by my aunt, who was the wife of the Superintendent from 1931 to 1960, Carey is known to have stayed at the Press. Just when, and for how long is not known.

(2) In J. C. Marshman a nephew of Ward's is mentioned living at an indigo factory in the interior. No mention is made of exactly where, but it is reasonable to speculate that it was Ward's nephew Nathaniel Ward, who he was visiting at Nuddea. (See Chapter 24)

(3) Towards the end of 1818, William H. Pearce founded a new Baptist Mission Press on the outskirts of Calcutta. Verbal tradition at the Press has it that a small chapel existed on the corner of Lower Circular Road and Elliott Road, on which a bookshop was later built. This must have served as the Mission Chapel until, in 1821, a Chapel, Manse and Field Secretary's house were built next door. Ward may have envisaged some of these plans when writing this letter. The site, which became the headquarters of the Baptist Mission, was on cheaper land to the east, considered by Europeans to be still part of Black Town, and attached to the new ring road called Upper and Lower Circular Road. According to a mid-nineteenth century map, buildings were only erected on the inside of the road, which gives the impression that the road was built as a defensive measure to move troops quickly to protect the north, east, and southern parts of the metropolis, inside the half-completed Mahratta Ditch.

(4) 'Sumachar Durpun'. Today this would be spelt 'Samachar Darpan'.

(5) 'Dig-dursun'. Today this would be spelt 'Dig-darshan'.