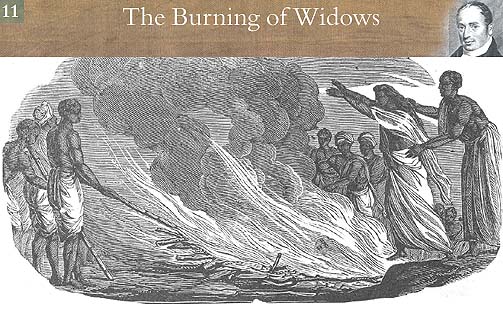

'Burning of Widows', an illustration from an American edition of 'A view of the History, Literature and Religion of the Hindoos', by William Ward, Hartford, 1824. Courtesy Derby Local Studies Library.

At the start of the year, 1804, the staff were augmented by 4 new missionaries from England, Rev. William Moore, Joshua Rowe, John Biss and John Mardon. Permission was still not possible for missionaries to travel on Company vessels, and so they had travelled via America and Madras. They landed in Calcutta without any molestation and proceeded to Serampore. The converts welcomed their 4 additional friends with what appeared to be a love-feast. After a meeting of thanksgiving, the Christian community in Serampore sat down, 50 in number, to an evening of Bengali entertainment.

The Mission was now straightened for accommodation as the community consisted of 8 families, including Felix Carey who was now recently married. The school had considerably increased, and the Printing Office required enlargement. Premises to the east of the chapel were now offered for sale and they were purchased without hesitation. The 3 parcels of ground which became the Mission premises had thus cost about £3,000, or less than the amount of their net income for 2 years (1).

Carey revived a plan for the translation of the 'Ramayana' (the Iliad of the Sanskrit language), funded by Fort William College and the Asiatic Society. This was a most arduous undertaking, which was now added to the labours of Carey and Marshman, but consolation was provided by the thought that the project would finance at least 1 missionary station.

Ward writes to friends on 27th December 1806:

'The Mission goes on as usual though we have met a check with the English governor. Brother Biss is going home on account of bad health. We are building a chapel in Calcutta; I might say two chapels. We baptize now and then, and the translations are proceeding. Brother Mardon and Chater are going to the Burman empire.'

Suttee Since residing at Serampore the missionaries had long contemplated with painful interest the immolation of widows. In 1803, Ward had written 'A horrible day, - the Churak Poojah, and three women burnt with their husbands, on one pile, near our house.

In his book 'A View of the History, Literature and Mythology of the Hindoos', Ward describes the practice in painful detail.

'When the husband is directed by the physician to be carried to the river side, there being no hopes of his recovery, the wife declares her resolution to be burnt with him. In this case, she is treated with great respect by her neighbours, who bring her delicate food, &c. and when the husband is dead, she again declares her resolution to be burnt with his body. Having broken a small branch from the mango tree, she takes it with her, and proceeds to the body, where she sits down. The barber then paints her feet red; after which she bathes, and puts on new clothes. During these preparations, the drum beats a sound, by which it is known, that a widow is about to be burnt with the corpse of her husband. On hearing this all the village assembles. The son, or if there be no son, a relation, or the head man of the village, provides the articles necessary for the ceremony.

A hole is first dug in the ground, round which stakes are driven into the earth, and thick green stakes laid across to form a kind of bed; and upon these are laid, in abundance, dry faggots, hemp, clarified butter, pitch etc. The officiating brahmin now causes the widow to repeat the formulas, in which she prays, that "as long as fourteen Indrus reign, or as many years as there are hairs on her head, she may abide in heaven with her husband; that the heavenly dancers during this time may wait on her and her husband, and that by this act of merit all the ancestors of her father, mother, and husband, may ascend heaven." She now presents her ornaments to her friends, ties some red cotton on both wrists, puts two new combs in her hair, paints her forehead, and takes into the end of the cloth that she wears some parched rice and kourees.

While this is going forward, the dead body is anointed with clarified butter and bathed, prayers are repeated over it, and it is dressed in new clothes. The son next takes a handful of boiled rice, prepared for the purpose, and, repeating an incantation, offers it in the name of the deceased father. Ropes and another piece of cloth are spread upon the wood, and the dead body is laid upon the pile. The widow then walks around the pile seven times, strewing parched rice and kourees as she goes, which some of the spectators endeavour to catch, under the idea they will cure diseases.

The widow now ascends the fatal pile, or rather throws herself down upon it by the side of the dead body. A few female ornaments having been laid over her; the ropes are drawn over the bodies which are tied together, and faggots placed upon them. The son, then, averting his head, puts fire to the face of his father, and at the same moment several persons light the pile at different sides, when women, relations, &c. set up a cry: more faggots are now thrown upon the pile with haste, and two bamboo levers are brought over the whole, to hold down the bodies and the pile. Several persons are employed in holding down these levers, and others in throwing water upon them, that they may not be scorched. While the fire is burning, more clarified butter, pitch, and faggots, are thrown into it, till the bodies are consumed. It may take about two hours before the whole is burnt, but I conceive the woman must be dead in a few minutes after the fire has been kindled.' (2)

The missionaries had made repeated attempts to draw government attention to suttee but it was regarded as one of the characteristic features of Indian society. Little was known about it in England, and Europeans in India were unaware of how prevalent it was.

The missionaries decided that the first step towards its abolition was to make the public aware of the number of victims. In 1803 they employed natives to travel from place to place, within a circle of 30 miles of Calcutta, and the number of cases of suttee was found to be 400 in that year.

The next year, 1804, 10 agents were stationed within the same circle, at different places on the banks of the river, and they continued there for 6 months to get a more accurate record. They counted 300. Carey asked the pundits at Fort William College to collect extracts from the shastras connected with this practice. They showed that 'suttee' was countenanced rather than commanded. These facts were put in the hands of Mr. Udny, the philanthropic Member of Council, which he submitted to Lord Wellesley. Unfortunately the Governor-General was to leave office within 7 days and no action was taken. The question was postponed for another quarter of a century and a further 20,000 victims ascended the funeral pyre.

On 14th December, 1804, Ward writes:

'There have been no letters received at the post-office till just now, and now I am writing night and day. However, I am sorry from my heart, that I have not embraced some earlier opportunity. In the hot weather I feel no heart to write letters, and indeed I have been very ill for some time past. I am now in good health and spirits, and so is my family.

You say G. sighs much - If sincere, I have no objection, there is little fear of being religious over much; I fear more from a worldly spirit, than from spending too much time in prayer and meditation. Excess in religious feelings is to be avoided; but the danger of man is greatest on the other side. His nature, his habits, his companions are sinful; and he who carries real piety to its highest attainments in the strength of God, does more than conquer the world. I know I have never been in danger of being righteous over-much; I confess with shame, that my religious feelings have been too cold and lukewarm; so that I have often doubted, whether I have been truly converted or not, on this account.

Our family has been this year in general health; but we have to lament the loss of our dear sister Chamberlain, at Cutwa. She died a few days after her lying-in; the infant is living. I had for some months an intermitting fever hanging upon me, but I am now in good health, and so is Mrs. Ward. My little Hannah comes on apace; she is now 14 months old; begins to talk, and has a hundred little tricks. She has great spirits, and I am afraid will want frequent restraint. I was once crying over her as a dead child some months ago; but God revived her.

We have baptized more this year than in any former one; but we have had much trouble with some of our members, and one or two have been excluded.

The chief sins of the natives are lying, covetousness, and deceit. They are over-reaching in all their dealings, asking twice as much as they will take. They are very obsequious, where they have any hopes of gain, and very insolent and haughty to inferiors; they are excessively greedy, when they have any prospect of a customer. The market places are called bazaars, and so are the streets, which contain nothing but shops. Hence at Calcutta, there is lol-bazaar; there is the red-bazaar; the Chinee-bazaar, that in which Chinese things are sold. At these shops, the shopkeepers, standing at the doors, call out to the passengers in broken English, 'Master, got very good ting!' 'master, I got very good stockings; master want any ting; I serve master.' Some of the natives of Calcutta are very rich. Some ride in carriages like the English, and others in palanquins. Their great expences are weddings, in worshipping their idols, or in making feasts for the Brahmins. The expence in worshipping idols, lies chiefly in making, guilding, and adorning the image, in employing singers and dancers, in feeding all the neighbouring Brahmins, and in making presents.

I have lately been out on a journey for twelve days. I rode in a palanquin carried by four men at a time, called bearers. A number of native brethren accompanied me on foot. I had eight bearers; first, four carried me a short distance, and then, the other four. The palanquin is a kind of box, with a pole at each end, which rests on the bearers' shoulders; it stands on four short legs, is matted at the bottom, and on the sides are sliding windows or French blinds. The last day I was out, the bearers carried me 24 miles, and I afterwards came as many more on the river, by boat. Here are no good roads, except what have been made by the English; we are obliged either to ford rivers, or go over in boats; there are no bridges. The method of travelling by palanquin is expensive: I gave the bearers about six shillings and six pence a day; besides them I had to take three carriers, to carry food, cooking things, cups, plates, knives &c. these three men had two shillings and sixpence per day; In the palanquins you may either sit or lie down at night. I slept in mine under a hovel, or in a yard perhaps; the men under a tree.

It is too hot to walk; if you go on horseback it would be too hot, and you have no place to sleep at night. We mostly travel by boat; but in some parts there is no river, and then you must go by palanquins. I went to see two native brethren, and stayed at their houses two days. On the road I talked at different places, and gave away tracts, and in the places, where our brethren lived, I talked to many.

In going to see a native brother, you cannot go and sit down at the table with him, and take a bed with him. He eats on the ground, off a dish or a plantin leaf, and he has no bedstead, perhaps, but lies on the floor or a mat. He eats food you have not been used to; but he can get you fruit, milk, eggs, fowls, sugar, &c. The Hindoos have a great abhorence of fowls, the same as Mussulmans have of pigs. Because I bought fowls for my food, they laughed at our native brethren and said, I was come to make them eat fowls. They also have a great abhorrance of fowls eggs. They try to insult our native brethren, by saying to them, 'Ah! now you eat with the English - you eat cow's flesh, and fowl's eggs.' These words mean no harm to us; but they reflect great disgrace, on whomsoever they fall, in their eyes. We live in a state of great ease and comfort; yet I know, we have no superfluities; we eat only that, which we have earned by great industry. No Europeans in this country work as we do. The money sent by the Society does not half meet our expenditure.'

The journey alluded to in the letter was a trip to Jessore, accompanied by 8 or 9 native brethren, most of them preachers. The result of this tour was that several natives went to Serampore, were instructed, baptised, and joined the church.

The church at Serampore had, for 5 years, adhered to the practice of 'strict communion', that is, that none but those who had been baptised by immersion, were admitted to the Lord's Supper. Ward and Marshman were open communionists when they left England, but Carey had inbibed the principle of 'strict communion' from Andrew Fuller, and the other ministers in Northamptonshire, and on the formation of the Church at Serampore, persuaded his colleagues to adopt it. Captain Wickes, the captain of the 'Criterion', on his return to Bengal, was informed that the rules of the Church no longer permitted him to join them in Communion. Ward, in particular, deplored this rigid, and, as he thought, unlovely proceeding, though he considered it his duty not to disturb the harmony of the Church and Mission. But after Mr. Brown, the Senior Chaplain, and head of the ecclesiastical department of the Presidency, had taken up permanent residence in Serampore, the subject frequently came up for discussion, and Ward urged reconsideration of a rule that debarred many Christian friends from partaking of the Sacrament at the Mission Chapel. Marshman was influenced by these arguments and brought Carey round to the same view.

Ward recorded in his journal that the alteration was not affected by his arguments, though he should have thought it an honour if it had been so; that their newly arrived brethren had adopted it cheerfully, and that all the sisters had been previously 'on the amiable side of the question. I rejoice that the first Baptist church in Bengal has shaken off that apparent moroseness of temper which for so long made us appear unlovely in the sight of the Christian world. I am glad that this church considers real religion alone as the ground of admission to the Lord's table. With regard to a church state, a stricter union may be required; but to partake of the Lord's Supper worthily, it requires only that a man's heart be right toward's God.'

In 1811 this decision was reversed when Marshman was persuaded by a long and detailed correspondence between Ward and Fuller. Marshman was convinced by Fuller's arguments in favour of 'closed communion'. The other missionaries sided with Marshman and Ward gave way with good grace.

Fluctuating fortunes regarding converts During 1805 there was cause for disappointment and rejoicing. In March they 'regret the low state of things among them - no enquirers - and no new converts.' Soon after they remark that every enquirer had left them clandestinely. The misconduct of some, and the profligacy of others, disgraced the cause in the eyes of the Bengalis, and inflicted the deepest distress on the feelings of the missionaries.

In June, the first baptism was carried out at Cutwa, and two enquirers came forth in Jessore, both of whom were baptised. By the end of October 15 enquirers came forward in, or around, Calcutta, all of whom were baptised by the end of the year. The total number of additions to the church in this year, which had started with so little promise, was 34, 30 of whom were adult natives.

On the 9th September, 1805, William Carey Jr, and Mr Moore went on a missionary tour through Eastern Bengal as far as Dacca. For the first 70 miles of their journey they found that people had already seen the tracts, but beyond that distance their message was novel and strange, though it was received with evident interest. On reaching Dacca they began to preach and circulate tracts. The people thronged to their boats by the hundreds and they were obliged to push off from the shore, but the crowd pressed through the water and, in the course of an hour and a half, 4,000 tracts were given away. The next morning they went into the heart of the city and were stopped by order of a Magistrate who demanded to see their passports. Finding they had none to show, they were reminded of the consequences of Europeans travelling without one. The Magistrate was joined by the Collector, and they declared that the tracts created much uneasiness in the minds of the people. The missionaries were therefore to desist from the work and leave the city. They returned forthwith to Serampore.

A few months later, in November 1805, William Ward went to Jessore to procure land for a missionary settlement. In a letter to Stennett dated '13th November, 1805, Mission Boat, going into Jessore', Ward writes:

'I am now accompanying brother Mardon into Jessore; we have been out a week. We have been obliged to come through the Sunderbunds on account of water, as the smaller brooks do not contain water enough for boats. We have a small budgerow, (a boat with venetian windows) with four rowers and a helmsman; we also have a cook boat with us. We are going to fix on a spot for a mission settlement. Ten or twelve persons have been baptized from this district, and we have hopes, that the cause may flourish here. We have another mission settlement at a small place called Cutwa, in the district of Burdwan. We are just going to form another at Dinagepore, whither brother Biss is going.

Last Lord's day week we baptized ten natives, five men and five women, one a Brahmin, another a Kaisthu, the rest Soodrees. several of these were the fruits of some tracts and a Testament, which I gave away in a village near Calcutta four years ago; one of the women was Anunda, the wife of Krishnu Presaud; she dated her change of mind from a sermon, that I preached at the Bengalee school about four months ago.

We have much reason for thankfulness to God for the great portion of health we have enjoyed, and for the happy progress of all our plans. We want only men and money to fill the country with the knowledge of Christ. We have arrived at that point of our labours, that we can make them efficient, so far at least as human means go; we are neither working at uncertainty, nor afraid for the result. We have tried our weapons and know their strength; the doctrine of the cross is stronger than the cast, and in this we shall be more than conquerors. As we turn all gifts to account, as much as possible, and set our converts to work, as soon as they begin to walk, we have now more missionaries than you would expect. Including brother Fernandez, we have ten European Missionaries, and ten native Missionaries, most of whom have been useful to others, and some of them preach with great fluency. We shall fix a native itinerant or two at each of the stations, who, though they would be able to do nothing by themselves, yet in connection with an English brother may do a thousand times more than he would alone.

A new chapel, in which we shall have the greatest share, will soon be erected at Calcutta. About 8 or 900 ruppees are subscribed. (3)

Ward attempts to set up a missionary settlement at Jessore In Jessore he was received with courtesy by the Judge, and accommodated in a side room of the Sessions House. The Judge thought the Hindu religion very innocent, and Mohammedanism so like Christianity there was little to choose between them.

Ward was advised that the missionaries should, in the first instance, apply for leave from the Government to settle at the station, but he replied that such an application was more likely to receive a special refusal than a special license. The other European officers of the station were unwilling that missionary labours should be brought so near them lest the public tranquillity and their own ease, should be disturbed. Ward was enabled at length to fix on a spot that was sufficiently near the Courts to afford the missionary official protection, but not too close to their residences to offend their sensibilities. But when he was on the point of concluding the agreement it was pointed out that, to be valid, it had to be registered at the Collectorate, and the Collector refused to register it till permission could be obtained from the Government that a missionary could reside in the district. Ward was obliged to return to Serampore without having accomplished his object.

Andrew Fuller puts the Plan for Translations into action The missionaries had proposed to Fuller that if he could raise £1,000 a year they could translate and print the Bible, or portions of it, in 7 of the languages of India. He decided to introduce the subject to the public and raise the funds. He travelled 1,300 miles through the northern counties of England, and into Scotland, preaching 50 sermons. The plan was as attractive to Episcopalians, Methodists, Presbyterians, Independents, as well as Baptists. He succeeding in raising £1,300, which was sent to India via America, where a further £700 was added to the total.

In April 1806 Carey embarked on the translation of the New Testament into Sanskrit, Mahratti and Oriya, soon after Hindi and Persian were added.

Ward's concern lest overambitious translations divert them from their missionary work The great undertaking can be said to have originated with the enthusiasm of William Carey, urged forward by the fervent co-operation of Joshua Marshman, and the warm encouragement of Mr. Brown and Mr. Buchanan. But there was one person who was concerned. Ward was prepared to support their efforts completely, and to work the Press with redoubled vigour, but he was concerned that this work would take them away from the actual missionary work that was before them. He records a minute:

'I recommend to brother Carey and Marshman to enter upon the translations which we can distribute with our own hands, and which may be fitted for stations which we ourselves can occupy. As to making Bibles for other missionaries, I recommend them to be cautious lest they should be wasting time and life on that which every vicissitude may frustrate. I tell them that the Jesuit missionaries have made grammars, dictionaries, and translations in abundance, which are now rotting in the libraries of Rome. I remind them that life is short, that this life may evaporate in schemes of translations for China, Bootan, the Mahratta country, &c., while the good in our hands and at our doors remains undone. I urge them to push things which are in our power, and, under Providence, at our own command. By spending so much of our time on translations which we can never distribute, we may leave undone translations nearer home, and leave the Mission at our deaths in such an unestablished state that all may come to nothing; whereas if it be once well established and pretty extensively established in Bengal, this will secure all these translations and everything else within proper time.'

Despite the minute, at the beginning of 1806, Joshua Marshman commenced the study of Chinese with a view to translating the Bible into that language. Mr. Buchanan engaged Johannes Lassar, an Armenian born at Macao, to translate the New Testament. He removed to Serampore and gave oral instruction to Marshman. For 15 years Marshman spent every spare moment on this wearisome task and he has the merit of carrying the first Chinese translation of the Scriptures through the Press. The translation was imperfect, and his son John Clark Marshman comments: 'At this distance in time (1859), however, on an impartial review of the wants of the Serampore Mission, the appropriation of Mr. Marshman's strength to a distant object of doubtful expediency cannot be regarded without some feeling of regret.'

Lord Wellesley was replaced by Lord Cornwallis. At the age of 65, Cornwallis was opposed to everything that Wellesley had stood for, and his appointment was considered by the Court of Directors of the East India Company as the strongest practical condemnation of Lord Wellesley. Lord Cornwallis proceeded to the north-west provinces, and at Gazeepore he died, 2 months after landing in India. He was the only Governor-General to die and be buried in India and, curiously, as he had no chaplain he had no funeral service.

He was succeeded by Sir George Barlow, a company man, who had been 27 years in its service. Initially he upheld the liberal principles of Wellesley. It was even hoped he would follow in his footsteps, but under his irresolute leadership the voices of the old India hands on the Council prevailed. The difficulties of the missionaries date from his appointment, and they were exposed to the storms of opposition for the next 8 years. Eventually the House of Commons took the question out of the Governor-General's hands in 1813.

Sir George Barlow also proceeded to the north-west provinces on his appointment and, in his absence, the administration was placed in the hands of the friend of the missionaries, Mr. Udny. The previous year, Carey had placed in front of him a statement of wishes regarding the establishment of Mission stations. Carey now pressed the plan on Mr. Udny, whose views were entirely in accordance with the statement, and pressed it on Sir George Barlow on his return. Barlow could not agree to something that was so contrary to the wishes of the Court of Directors in London and Mr. Udny had to convey this message to Carey. Carey's response was that, however great might be the respect of the missionaries for the wishes of the Government, 'they must form stations', and if they were unable to obtain Government approval, they were prepared to take the consequences on themselves.

The senior missionaries determined, without further hesitation, to send Mr. Felix Carey and Mr. Rowe to Benares and Mr. Mardon to Juggernath. Mr. Biss and Mr. Moore were sent to Dinagepore without a passport or license.

'Everything in this case, depends on the Judge of Dinagepore; if he should be mute, everything will be favourable,' writes Ward.

The Judge, Mr. James Prattle, who was never disposed to be mute on any occasion in his life, demanded to know whether they had authority from Government to proceed into the interior of the country. Finding that they had no such sanction he demanded they return to Serampore.

The first Brahmin convert, Krishna-Prisad, who had accompanied Biss and Moore to Dinagepore, died at Berhampore on his way back. The report of his death created a feeling of deep regret at Serampore, and the Bengali congregation were melted to tears when Ward, in the funeral sermon, drew a picture of his exemplary life, and the loveliness of his character.

In June, 1807, the first sheet of the Sanskrit New Testament came off the press at Serampore, with the new fount of Nagree type. Ward was particularly eager that this work should be urged forward with all diligence. He argued that this language, the great parent of all the vernacular languages of India, would facilitate other translations, since the pundits in every part of India were familiar with this classical tongue, and might be expected to use this version to make good translations into their own languages. In addition to Sanskrit, Ward put to press Mahratti, Oriya, Persian and Hindi versions. The Sanskrit grammar Carey had been working on for several years was completed and published, as was the first volume of the translation of the 'Ramayan', the renowned epic of India. However the work was never completed, after publication of 3 quarto volumes, all further work was abandoned.

In 1807, Ward also put to press the first volume of his work on the habits, manners and religion of the Hindus, for which he had been making researches and collecting material since his arrival in India.

(1) It is worth relating the story of Mrs Ward's bonnet at this point. Considering the extreme economy of the missionary's standard of living in proportion to their contribution to Mission funds, Mrs Ward happened to mention, in a letter to one of her friends in England, the price she was obliged to pay for a bonnet out of the 40 shillings a month which she and her husband received for all of their living expenses. The subject was brought forward for discussion at a Committee Meeting of the Baptist Missionary Society, in England, and the price was said to be "enormous". The remarks made were so indelicate that Andrew Fuller suggested that Mrs Ward be more cautious in her communications with England in future.

(2) 'A View of the History, Literature and Mythology of the Hindoos. Including a minute description of their Manners and Customs'. By W. Ward. Second Edition, carefully abridged and greatly improved. Volume 2, Serampore, printed at the Mission Press, 1815.

(3) A reference to the Bow Bazaar Chapel.