It is intriguing to think that while Ward was editing the 'Derby Mercury', and visiting churches outside Derby (amongst them Codnor, Nottingham and Burton), between Derby and Nottingham he would have passed an established Moravian Settlement at Ockbrook that had been in existence since 1739.

Carey used Moravian textbooks to establish the Mission at Serampore, and Ward relied on the Moravian model for guidance in times of trouble.

I have discovered no evidence, both in Moravian sources at Ockbrook, or from Stennett, that Ward made any contact with the Settlement at Ockbrook, but I have no doubt that he would have been aware of its existence, just 5 miles outside Derby, and knew of their beliefs. They had learnt how to live peacefully beside existing dominant doctrines and Ward drew on some of their wisdom to help the Mission family survive at Serampore.

The Moravian Church had its birth in 1457, in Bohemia, among the followers of the Church Reformer, Jan Hus. The emphasis was on simplicity in life and worship; for them Christianity was primarily a question of living in obedience to Jesus Christ, rather than applying a set of doctrines. Many people regard Jan Hus as the first Protestant. He had believed that the Scriptures were the highest authority and challenged the authority of the Pope, and that of the Catholic Church. He was burned at the stake in 1415.

Forty-two years after Hus's death, in 1457, a village community was formed to 'adhere to Protestant ideals, and live together in brotherly love, according to the example of the early Christian church.' The community separated themselves from the Papacy, and its priesthood, and set up a ministerial order of their own, according to the model of the early church. The Moravian Church became a Protestant episcopal church with strongly ecumenical views. Their views on education were particularly forward thinking.

In 1641, the Moravian Jan Amos Komensky (1592-1670), better known as Comenius, came to England at the invitation of both Houses of Parliament with a view to reforming education after the Civil War.

For nearly 200 years the Moravian Church was active in Central Europe, then came a period of intense persecution, during which time the brethren were driven underground. In 1722, refugees from Moravia and Bohemia settled on the estate of Count Zinzendorf, in Saxony. They built a village they called 'Herrnhut', and it was there that the Moravian Church came to life. Zinzendorf declared all Moravians to be 'truly unprejudiced against their Fellow Sisters (other churches), never taking part in their quarrels, never judging any Body, or its members.'

'Herrnhut' became a centre for missionary work, sending out missionaries to the West Indies, to the 'Eskimos' of Labrador, the 'Red Indians' of North America, and to many other places - including Serampore. The Moravians made contacts in England, and had a considerable influence on John Wesley.

It was not the Moravian's intention to set themselves up as a separate Church. Many Moravian Societies were formed as men and women sought greater spiritual depth in their religious life. Eventually a few of these became churches, but mostly, members of Societies stayed members of the Church of England and continued to attend their own parish churches. For this reason the Moravian Church remained a small denomination, though recognised by Act of Parliament, in 1749, as 'an ancient, protestant, episcopal church.'

This non-proselytizing policy led a number of Anglican clergymen, concerned about the spiritual poverty of early 18th century England, to ask the Moravians for help.

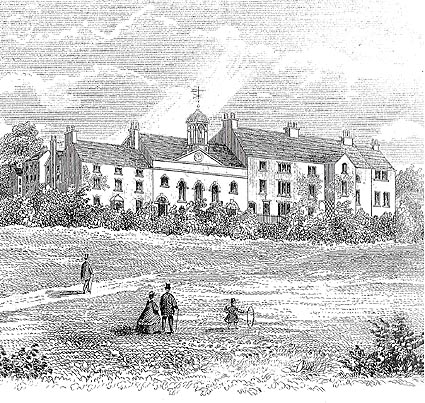

The Moravian Settlement at Ockbrook. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Moravian Church - British Province.

The Moravian Settlement today.

More views. Click on the images.

New forms of religious practice were taking hold in England during the 'Age of Enlightenment' when a new self confidence was emerging to challenge the established church. Individuals felt a new freedom to express their religious views and to decide for themselves how they should interpret Scripture. They became known as Dissenters, ie. they dissented from attendance at Anglican services.

Only Anglicans could enter universities or hold many public offices. They were also the only ones to have the legal right to baptise infants, bury the dead, and marry the living.

Moravians saw the need to settle in sharply defined communities, relatively free of interference from civic and national conformity, while maintaining good relations with their neighbours.

In 1739, an Ockbrook man, Isaac Frearson, was in Nottingham on business. In passing the Market Cross he stopped to listen to a preacher. This was Rev. Jacob Rogers, curate of St. Paul's, Bedford, who had already come into close contact with the Moravians in London. Frearson invited Rogers back to Ockbrook, where he preached in his barn.

A New Plan of the Town of Nottingham, 1744, showing the Malt Cross in the Market Place, the likely spot where Rev, Jacob Rogers was preaching. Courtesy Nottingham City Libraries, Local Studies Library. Click here to see a more detailed version of the map. The people of Ockbrook were, like most villages in England, poorly housed, badly fed, and had little knowledge of Christianity. Tubercolosis was rife, infant mortality high and outbreaks of smallpox were common.

During the next 10 years many of the villagers became members of the Society and many of them wished to form a Church. This was not lightly agreed to as it was against the original principle that had been laid down. Peter Böhler, the Superintendent of the work in Britain, came from London, spoke individually to all the people concerned, and eventually yielded to the request. On 24th September 1759, a congregation of the Moravian Church was formed.

The estate of Isaac Frearson was bought and a Church built. From 1750 to 1757 the minister (the Moravian term is Brethren's Labourer) was John Ockershausen. The zeal and self-sacrifice which both he and his wife brought to their duties is remarkable. In addition to Ockbrook they served Nottingham, Little Eaton, Belper, Duffield, Draycott, Dale Abbey, Spondon, Sileby in Leicestershire, Wolverhampton and Sheffield. They journeyed on horseback or on foot, in all weathers, and both they and their successors lived truly dedicated lives.

In 1771 the Anglican Bishop visited Ockbrook and wrote 'Ockbrook has a hundred families, none of note and there were no Papists in the Parish or any perverted to Popery. There were neither Quakers, Presbyterians, Independents, Anabaptists nor Methodists, but there were some Moravians from distant places - none of rank - whose numbers were lessening of recent years.'

In the latter half of the 18th century, Ockbrook was the central point of the Moravian Church in England. There were constant comings and goings between Fulneck and Dukinfield in the north, and Bedford, Bristol and London to the south. Ockbrook was a natural halting place for travellers.

In 1825 the Synod of the Moravian Church moved its administrative headquarters to Ockbrook where it remained until 1875, by which time the claims of foreign Mission Fields made it a necessity to move the headquarters to London.

The aim of the Brethren was to make each congregation a 'village of the Lord'.

Each hour of the twenty-four had assigned to it, by Lot, a man and a woman volunteer to pray for that period. These were the 'Intercessors'.

The congregation must conduct themselves in such a way as to conform in all particulars to God's Will. Every matter of importance, even as personal a one as betrothal, had to be submitted to the direct decision of the Lord by means of the Lot. To the Lot were put three courses, affirmative, negative and blank. Either of the first two answers closed the matter, the third allowed of a further trial at a later date.

Discipline was strict and deviation from the standard laid down usually meant expulsion. In 1777 there was drawn up 'The Brotherly Agreement and Declaration concerning the Rules and Orders of the Brethren's Congregation of Ockbrook'. This was a moral code by which all matters, spiritual and secular, should be decided.

The Moravians divided the members of their congregation into sections called 'choirs', according to sex and marital status. Unmarried men and women could, if they wished, live and earn their living in respective Choir Houses for Single Brethren and Single Sisters.

In the men's house the trades practiced were wool-combing, worsted weaving, shoemaking, cabinet making, silk stocking weaving and baking. The sisters spun cotton for stocking making, embroidered on silk and they excelled at fine white needlework. Tradition has it that their most spectacular order was for a dress made of delicate muslin, with a design of white roses and ivy round the hem, and on a smaller scale on the bodice, for Queen Adelaide, the wife of William IV.

With the tradition behind them of John Amos Comenius, Bishop of the Moravian Church, and educationalist, as early as 1751 a little day school was set up for girls. A succession of small schools are mentioned in diaries over many years. These could only function in the spring and summer months as the roads were often impassable for children in winter.

A Girls Boarding School was founded in 1799, which, as Ockbrook School, still exists today.

The Moravians were invited by the Danish East India Company to establish a mission at Serampore, and in 1776 two missionaries, Br. Johannes Grassman and Br. Karl Friedrich Schmitt, were called to be stationed there. The Moravian Church's intention was to make preparations to establish a mission in the surrounding British territory, especially in Calcutta. However, their experience with the East India Company may have been an omen of the difficulties which the new missionary societies were to encounter. The East India Company would not allow permission for the Moravians to establish a mission in Calcutta, and one of the directors even warned that, without authorisation, their missionaries could be expelled on the director's orders as 'vagrants'!

However, they did manage to briefly gain an opening through a Danish trader who enabled the Moravians to station two missionaries at Patna for a period during the 1780's. But the Moravians finally conceded that they would be unable to obtain permission from the East India Company to establish any missions in Bengal.

Bishop Johann Friedrich Reichel was selected by the Unity's Elders Conference to undertake a thorough investigation, along with several volunteers, between June and October 1786 of the state of the missions and of their prospects in Bengal and the Nicobar Islands. It was decided that the outposts should be abandoned as there was little hope of establishing missions in the part of Bengal belonging to the East India Company. Also the missionaries found little time for preaching, when they had to earn their own living, and so would have even less chance of contacting the natives especially on account of the caste system. Patna was closed at once, the Nicobar Islands later, and Serampore in 1792. In 1795, the Moravian Church reluctantly decided to withdraw from the East Indies entirely, with the last of the missionaries returning home by 1802. (1)

It was when Carey was in his cobbler's workshop, with a map of the world pinned to the wall, composed of several sheets pasted together, that he became familiar with the Moravians. Notes on the characteristics, population and religion of every country as then known, were added to the map. He read of John Montgomery, and six other English Moravians in the West Indians; of John Rhodes and William Turner with the 'Eskimos' in Labrador. (2) From the first he had been a close reader of the Moravian Periodical Accounts. In an attempt to galvanise his fellow ministers into forming the Baptist Missionary Society, he wrote in 1792: 'See what Moravians are daring, and some of them British like ourselves, and many only artisan and poor! Can't we Baptists at least attempt something in fealty to the same Lord.' (3) Unlike the Baptists, the Moravians had their wealthy benefactor, Count Zinzendorf, behind them.

Carey, Marshman and Ward founded the Mission at Serampore, in 1800, on the accepted textbook of Moravian Missions - 'Instructions', by Bishop Spangenberg, published in English in 1788. (4) (5) Carey made an exception in one particular. In the textbook it lays down that 'each Settlement should appoint a Head or Housefather, to whom the rest should in love be subject.' He founded Serampore on equality for each, pre-eminence for none; rule by majority, and submission to that rule. He would have them call no man master.

When, in 1807, Lord Minto's order for the missionaries to remove their Press to Calcutta arrived. The Danish Governor was for inaction, Carey was helpless and in tears. It was Ward who had the cool head and set the course for the eventual relaxation of the ban with his reminder of basic Moravian principles. He reminded his fellow missionaries that 'Moravians never omitted to cultivate a good understanding with the Governors, wherever their missions were planted, by making themselves personally known to them, and explaining their plans of operation. Thus, said he, prejudices are disarmed, and the designs of the enemies baffled'. (6) It was Ward's leadership that brought the Serampore missionaries through this most severe of crises. It was not to be the last time the missionaries needed Ward's clear-sighted leadership. The destruction of the Press by fire, in 1812, was an even greater test.

The history of the Moravians, the Moravian Settlement at Ockbrook and the details of the Moravian activity at Serampore, Calcutta and Patna are reproduced with the kind permission of the Moravian Church - British Province. Sources: 'Ockbrook Moravian Church and Settlement, 1750 - 1975' by Alan McGibbon and Fred Linyard. 'Bold shall I Stand, the Education of Young Woman in the Moravian Settlement at Ockbrook since 1799' by James Muckle, published by Ockbrook School, The Settlement, Ockbrook, Derbyshire. 'William Carey', by S. Pearce Carey, Hodder & Stoughton, 1923. 'The Life and Times of Carey, Marshman and Ward', by John Clark Marshman, 1859.

(1) Text courtesy Lorraine Parsons, Archivist, Moravian Church - British Province.

(2) Page 12; 'William Carey', by S. Pearce Carey, Hodder & Stoughton, 1923.

(3) Page 90; 'William Carey', by S. Pearce Carey, Hodder & Stoughton, 1923.

(4) 'An Account of the manner in which the Protestant Church of Unitas Fratrum or United Brethren preach the Gospel, and carry on their Missions among the Heathen'.

(5) Page 186; 'William Carey', by S. Pearce Carey, Hodder & Stoughton, 1923.

(6) Page 321; 'The Life and Times of Carey, Marshman and Ward', by John Clark Marshman, 1859.

Return to Miscellaneous