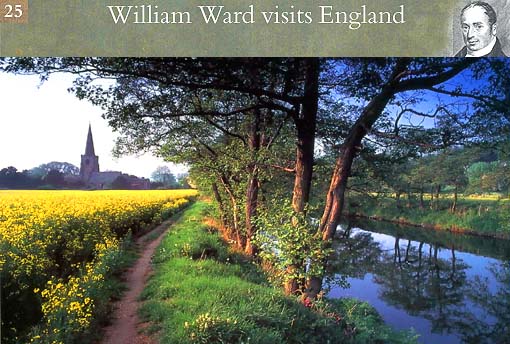

The English countryside at Duffield, a few miles north of Derby. (1)

Sir Stamford Raffles had returned to England on the return of Java to the Dutch, and was soon nominated to the residency of Bencoolen. Sir Stamford came around to Bengal on his way to Bencoolen, and passed some time at Serampore. He urged his friends to establish a mission station at Bencoolen, which he engaged to support with the full extent of his power.

There was, at the time, a nephew of William Ward's, a youth of energetic and enterprising spirit, residing at an indigo factory in the interior of the country, who, on hearing of Sir Stamford Raffle's proposal, volunteered to accompany him. The missionaries at Serampore never omitted any opportunity of establishing a press, for they considered it one of the distinguishing characteristics of the missionary enterprise, that, 'wherever a missionary goes he prints.' A press and types, and the necessary apparatus for printing the Scriptures and school books in the Malay language, were made up with great expedition; and in November 1818, Mr. Nathaniel Ward accompanied Sir Stamford to Bencoolen, where he continued to labour in the cause of improvement till the British settlements on the island were made over to the Dutch in 1826.

Ward's incessant labours had now begun to seriously to affect his health. It was 19 years since he had landed in Bengal, and his mental and physical exertions were greater than a European constitution could sustain continuously in that tropical climate. The excursion to Dacca and Chittagong had produced only temporary relief, and his medical advisors insisted on a voyage to England. It was with great reluctance that he consented to quit his colleagues at a time when the embarrassments of their position were beginning to thicken. But it was hoped that the visit to England would serve the double purpose of restoring health, and healing the breach with the Society, by personal and friendly intercourse.

He embarked on 13th December, 1818. Marshman took his place in the management of the Printing Office and the secular department of the mission. Ward employed the leisure of the voyage in reviewing the questions upon which he and his colleagues were at issue with the Society, and examining the future prospects of the missionary institution at Serampore.

On the propriety of having resisted the demand for trustees, his mind had never wavered. But he regretted that no adequate provision had been made to perpetuate the missionary establishment after their death.

During the early part of the voyage, when his frame was invigorated by the novelty of leisure and the sea breezes, he employed his time in composing 'Reflections on the Word of God for every day in the year, to be used in family devotions.' (2) He applied to his work with the usual ardour, and wrote 400 pages in 70 days. As the voyage drew to a close, the benefit he had at first derived from it was neutralised by a return of his old complaint, with the addition of dropsical symptoms. A diseased body acting on the mind created morbid feelings of anxiety, and gloomy forebodings of the disgrace which would cover his memory unless some 'settlement' was made at Serampore which would 'enable him to die an honest man.' The possibility of separation from his brethren he contemplated with intense pain: 'There seems to be a propriety that persons engaged in such a way as we have done should die at their posts.' Then, in the confidence that his colleagues could not fail to accede to his wishes, he dwelt with delight on the prospects of his return, and projected a 'History of Hindoo Philosophy', and desired that the pundits might be set to work to make translations from the works of the different schools, to be ready by the time of his return.

During the passage he was especially anxious to impress on his fellow passengers and crew the things that belonged to their eternal peace. Several persons dated their first serious impressions from his conversations and preaching during the voyage.

While writing his biography, Stennett received the following letter, dated July 1825, from someone who was with Ward on the journey:

'As I made a passage with Mr. Ward on board ship, from India to England, and consequently had an opportunity of knowing something of his habits, I feel much pleasure in giving you all the information I possess regarding your departed, worthy friend.

'During the whole voyage he sustained the character of peace-maker, and his own mind seemed to be absorbed in doing good to his fellow creatures. When any misunderstanding took place between persons on board, he seemed uneasy, until the wounds were healed, which his kind instruction and gentle rebukes contributed, in no small measure, to effect. He always declared the truth to us on the first day of the week, when the weather and his health would permit; at those seasons he appeared much affected, and laboured hard to impress upon his hearers the importance of the Gospel of Christ. The fallen state of man, and the necessity of a Saviour, were doctrines which he continually enforced, both in public and in private, in the cabin and among the seamen. To the latter he took opportunities of speaking in private, when they were at leisure; they respected him more than any other person I had ever observed in the capacity of passenger, either in this voyage or any other, and I have reason to believe, that the bread, thus cast upon the waters by that affectionate and exemplary follower of the Lamb, was found after many days bringing forth fruit, which will be to him a crown of rejoicing for ever, more especially as the seed had apparently taken root where he least expected, in the deepest part of the waters, where the sea was boisterous, and the prince of darkness had the strongest entrenchments.

'As a proof of the good, which his Master made him the instrument of accomplishing among the neglected part of the British community, those that go down to the sea in ships, it may be observed, that three of the seamen, who returned with him, have been baptized and united to churches; three more of their intimate seafaring friends, and three females in their families have followed their example. More also are now enquiring, and praising the Lord for his mercy and truth, but lamenting the loss of that beloved and distinguished servant of God. He seemed to feel much for the wicked state, in which he found seamen, and on one occasion begged, as a favour, that the steward might be restrained from swearing in the cabin, as it made his 'very blood run cold.' He pointed out its heinousness in the sight of God, and this had a very good effect, as several of the officers were present, by some of whom it has not been forgotten to this day. He lamented, also, very much over the idolatrous state of India.

'His habits were rather retiring; he read and studied much; he rose early and perused the New Testament before breakfast, and was employed in the cabin the whole of the forenoons and afternoons; in the evenings he refreshed himself in the open air on deck for an hour or two, when he frequently got into conversation with some of the unemployed sailors; after which he returned to his cabin, where he again laboured until ten or eleven o'clock, and then retired.

'He spoke much of England, and longed to arrive in time to attend the annual meeting of the Bible Society. He had the interest of his native country much at heart; when speaking of her grandeur, &c. he used frequently to say, 'She is great, she is rich; oh that she may be good; for she is the highly favoured land.'

'I could write much about his affectionate exhortations, but this will suffice.'

William Ward landed in England in May, 1819, enfeebled rather than strengthened by the voyage, and proceeded to Bristol, to his friend Dr. Ryland, who was so greatly alarmed by his jaundiced appearance, as to call in medical advice without delay.

Ward found that Dr. Ryland retained all his warmth of affection for Serampore. The Society itself was torn with factious dissensions; it was divided, as Ward learned into 5 parties, consisting respectively those who were anxious to retain the seat in Northamptonshire, and those who were for transferring it to London; of the old men clinging on to the cherished associations with Serampore, and the younger men who corresponded with, and supported, the Junior Brethren; and a neutral section who were disgusted with the proceedings of the Committee since the death of Andrew Fuller.

Ward's intercourse with Dr. Ryland induced him to urge on his brethren, with increased earnestness, the necessity of the 'settlement' he proposed.

'Let it clearly and unequivocally meet the case, so as to secure a constant succession of the three members of the union at Serampore, so that in case of neglect to fill up vacancies, the society may have that right; and that property may revert to the society if the union should be dissolved. I know, my dear brethren, that my retirement will be no loss to Serampore, and I will not therefore threaten you with this resolution; but I cannot, I dare not, return until you take the step I have suggested. But oh, my God! do thou prevent this rupture, do thou put in the hearts of my brethren that holy disinterestedness of feeling that shall make them, with all their hearts, go into the plan of securing to Thee the result of the exertion of their lives; that still Serampore may be Thine, that from thence for centuries to come the word of God may go forth, and 'run and be glorified.' Oh, let it be a house for God as long as a single wall shall be left standing, essentially contributing year by year to the grand result - the conversion of India.'

Having become to some degree convalescent, Ward ventured to travel thoughout the country. In one of his letters to Serampore he stated that if matters had been straight between Serampore and the Society he might have raised £6,000 with ease for the college, but so sinister an impression had been created in England and Scotland, that contributors hesitated even to give to the Society.

Ward visited Mr. King in Birmingham, who had assisted at the formation of the society, and had acted for some time as treasurer, and obtained from him a copious narrative of the reports in circulation against the Serampore missionaries. He said they were charged with having amassed colossal fortunes amidst all their professions of disinterestedness, and that it was generally believed, throughout the denomination, that they were no longer fit to be entrusted with public money. Ward was astounded at the variety and malignity of the reports which crowded in on him in every direction. Under the anguish created by his conversation with Mr. King he gave vent to his wounded feelings in the following strain:

'If you do not, my dear brethren, open your eyes, and rouse yourselves to do what is right and what is easy, your end will be shame and not honour. My resolution is unalterably taken. I cannot die and leave things as they are. Save me from a separation. I do still want to die with you, and to labour at your side till I die. Did ever men place their affairs in such a state of suspicion, since the world begun, without a shadow of reason, and deliver up their fair characters to be spit upon, and themselves be spoken of as rogues by those who seek occasion against them, as we have done? Are we not doing everything for Him who 'loved us, and loved us to death?' Let us do it then in such a way that our friends may rejoice over us and we rejoice with them. Let us not drive them to the necessity of apologising for us, and making the best of our affairs, as though we were doing something dark, to give birth to future infamy.'

But Ward was never more mistaken than when he supposed that any arrangements he, or any of his colleagues might make, could silence these calumnies. Of this he was fully satisfied when he found that after his colleagues had cordially acquiesced in his proposal, and made the settlement which he had proposed to his entire satisfaction, they stood no fairer with the adverse members of their own denomination than before.

Shortly after Ward's arrival in England his complaint returned with increased violence, and obliged him to resort to the great sanatorium of diseased Indians at Cheltenham. (3) Though he derived much benefit from its waters, his physicians enjoined perfect repose; but he could not be dissuaded of availing himself of the first symptoms of returning health to advocate the cause of improvement in India. He was daily engaged, either on the platform or in the pulpit, in endeavouring to rouse public attention to this object.

Ward was the first missionary who had ever returned to England from the East, and his welcome was enthusiastic in every circle except one, where he encountered nothing but cold reserve. His animated addresses were eminently calculated to rivet the attention of popular assemblies, and the novelty of his statements gave a particular interest to his appearances in public; his engagements were therefore rapidly multiplied.

'I have,' he writes, 'all the attention and popularity which a greedy man could wish, but I sigh for home. One half hour in communion with God is far more precious than 'hear, hear,' echoed by a thousand voices at a public meeting.'

Ward's life in England was one of incessant activity. He superintended the publication of another edition of his history of the religion, manners, and philosophy of the Hindus. The printers supplied him with two sheets daily; and 'thus' he remarks, 'instead of coming home to leisure, I am plunged up to the neck in work.'

During the voyage he had drawn up an address to the British public, narrating the progress which had been made by the Serampore missionaries, in unison with the Baptist Missionary Society. He described their labours in the departments of preaching, translation, and schools. The 4th plan which they were now desirous of submitting to the public was the college, intended chiefly for the instruction of native teachers and pastors in secular and Christian knowledge. The salient point of Ward's argument was that the 150,000,000 of people in India could never be adequately supplied with missionary labourers from Europe. It was upon native agents that the weight of the work must eventually rest. It was difficult for a European to acquire the native language to such perfection that he could become a persuasive preacher. A native preacher could find such ready access to their hearts and minds as no European could expect to enjoy; he could subsist on the simplest food, and find a lodging in every village.

It was necessary that this appeal should be accredited to the public by the Baptist Missionary Society, but it was not without great importunity on the part of Ward and Dr. Ryland that they consented to give it their sanction. Ward was informed that the funds of the Society were at a low ebb and he agreed to devote his time, in the first instance, to the service of the Society, at a time when the impression he created had the charm of novelty and freshness.

He likewise made the most strenuous efforts to promote the establishment of female schools in India, and was among the first to awaken the public attention to this important branch of duty.

'It is beginning,' he writes 'to become an object of concern in this country. I started it at a meeting of the British and Foreign School Society; a record was made on the subject, and when Mr. Allen returned from the continent, he offered to advance the sums necessary to make a beginning. I rejoice in this, as one of the results of my visits to England.'

Ward also published an earnest appeal to the British public, on the atrocities of female immolation, and endeavoured to organise an association with the distinct object of pressing for its abolition.

'I hope' he writes to his friends in Serampore 'the question of these burnings will be taken up, and that these fires will burn no longer. We must inundate England with horrid tales, till the practice can be tolerated no longer.'

But the time had not arrived for extinguishing these fires and they were to be tolerated for 10 years more. (4)

He travels through England, Scotland and Wales to promote the college After having deferred for several months to the wishes of the Society regarding collections for the college he resolved to postpone this duty no longer. He visited the various counties and towns in England, and proceeded through Scotland and Wales, addressing large assemblies, and calling personally on the wealthy and the benevolent.

'I have realised,' he writes 'more than £3,000 for the college, of which £700 have been contributed in Scotland, which is to be devoted to the support of native preachers at the rate of £10 a year for each. It is not to be funded. The sum raised in England I shall place in trust, the interest to be annually transmitted to India, to be expended in training native preachers, and other Christian students. Perhaps I shall do the same with the money raised in America; and thus leave nest eggs in both countries. The buildings you must raise yourselves.'

The Society moves its headquarters to Fen Court, London 'London,' as Ward wrote to his colleagues 'had gained the prize.' The leading member of the new Committee was Mr. Joseph Guttridge. He had made an independent fortune, and having retired, took a prominent part in all the benevolent movements of the denomination.

The members of the new Committee devoted several months to the review of the correspondence which had passed for 25 years between Andrew Fuller and his friends at Serampore. At the end of 1819 they embodied their conclusions in a series of resolutions. They relinquished all intention of interfering with the management of affairs at Serampore. They proposed a consolidation of the trust deeds on such terms as should leave the premises in the exclusive possession of the missionaries at Serampore. They asked also for the power of proposing successors at Serampore, or a veto on the appointment. However, they stated that if they were to consent to the alienation of the property at Serampore from the Society, they would violate the confidence reposed in them by the public, and be guilty of a dereliction of duty.

Ward's letters written on the voyage, and the early ones from England, caused great surprise to his brethren at Serampore. He had cordially approved all their measures relative to the premises, and the maintenance of their independence, to the day of his departure. The new request which he urged on them with such painful importunity, had never occupied their attention, and they had trusted to Providence for successors. The 'settlement' he implored them to make appeared to involve the most formidable difficulties. It was not without reason that they exclaimed, on hearing what was expected of them in England, 'There is no king, lord, nor ruler that asketh such things of any magician, or astrologer, or Chaldean.' But they resolved to make an effort to meet the impassioned wishes of their colleague, and after long and anxious deliberation constructed a deed to meet his request.

The deed was satisfactory to Ward, though he thought it susceptible to some improvement. From the day of its arrival in England, every feeling of hesitation or anxiety regarding his return to Serampore was dispelled. Every letter breathed a spirit of the warmest affection for 'long lost, and longed-for Serampore,' as he called it; and he seemed to count the days that detained him from the 'dear old spot.' His attachment to his brethren became stronger than ever; and to rejoin them, 'never again to part,' was the uppermost thought in his mind.

But the document produced a different effect on the Committee. The clear determination which it exhibited, to maintain the independence of Serampore inviolate, created a feeling of consternation.

With the irreconcilable difference of opinion between the two bodies on a point of vital importance, Ward felt that it would be vain to entertain any hope of a cordial union. He appears to have renounced any further attempt to restore it, and all his subsequent movements had reference only to his return to Serampore.

It was 20 years, within a fortnight, since they first met at Serampore and read Fuller's farewell communication, in which he informed them that the funds of the Society would not allow him to promise more than £360 a year for the support of 6 families and found themselves driven by necessity to provide means for their own support. They had not only succeeded in this object, but during this period had acquired a surplus of £40,000 or £50,000, which they had devoted to the cause in which they were engaged. They had also been entrusted with the administration of public donations to the extent of £80,000.

It is easy to conceive the feelings with which men who had acted with such zeal and devotion would learn that, in their own land, and, in their own denomination, they were considered deficient in common honesty and unworthy of public trust. Men of generous hearts hesitated to support the Society lest their donations should find their way to Serampore. But they suppressed every indignant emotion, and sat down to the vindication of their characters with a degree of calmness which was scarcely to have been expected under such irritation.

(1) A path along the River Derwent, just north of Derby, with Duffield parish church in the distance. William may well have walked this path in his youth and the sights, smells and sounds would have stayed with him in Serampore. Rapeseed (seen in the field on the left) was grown in his time. The scene has hardly changed.

(2) A copy of this book is in the collection of the Derby Local Studies Library entitled 'Reflections on the Word of God for every Day of the Year', by the Rev. William Ward of Serampore. Printed for W. Simpkin and R. Marshall, Stationers' Court, Ludgate Street, London, 1835.

(3) The two volume second edition copy of 'A view of the History, Literature and Religion of the Hindoos' in the possession of the Derby Local Studies Library has the following handwritten inscriptions on the title pages: Volume 1. 'Cha Stuart, from the Author, Cheltenham, 1819'; Volume 2. 'Dr. Charles Stuart, with the Author's very affectionate regards, Cheltenham, Aug 9, 1819.' The imprint states that Volume 1 was printed at Serampore in 1818, and Volume 2 was printed at Serampore in 1815.

(4) In 1829 Lord William Bentinck landed in Calcutta as the new Governor-General with a stern and unalterable determination to end this atrocious rite immediately. He requested the opinion of the officers with the greatest experience and judgement as to the effect which the abolition might produce in the minds of the native army. A circular was sent to 43 military officers. There were various shades of opinion, but 28 of the 43 gave their support to the immediate abolition of the practice. A similar circular was sent to 12 of the most senior civil servants. Of these 9 were for immediate abolition. Some had even managed to extinguish it in their own districts. The King of Oudh and the Rajah of Tanjore had prohibited it with success. On 4th December, 1829, the regulation prohibiting suttees in the Bengal Presidency was passed. The practice was declared illegal and punishable in the criminal courts. Everyone aiding and abetting a suttee was deemed guilty of culpable homicide. An English and Bengali translation was to be published at the same time. It was dispatched to William Carey for translation on Saturday afternoon. Knowing that every day's delay might cost the lives of 2 victims he proceeded with haste. Instead of going into the pulpit on Sunday, Carey sent for his pundit and the translation was completed before night. The abolition left a deep sensation amongst the rich and influential Bengalis and an address of thanks was delivered to Lord Bentinck. The orthodox Hindus were astounded and enraged and they determined to deliver a counter memorial. 800 signatures were attached to it. A society was formed to restore the rite of suttee and they resolved to appeal the question in England. A sum of £1,100 was raised. Only 4 months after the Act it was reported that 25 acts had been prevented by the police without the smallest commotion. The sepoys heard of the abolition with profound indifference. Only 2 acts of suttee were recorded in the following 2 years. In 5 years suttee became a matter of history; and in less than 20 it was affirmed by Bengalis that it never existed. ('The Life and Times of Carey, Marshman and Ward', Volume 2,1859, John Clark Marshman.)