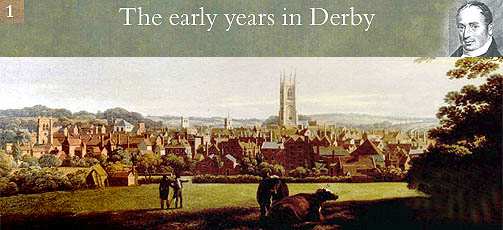

(1) Page 21, 'Citizen's

Derby', by W Alfred Richardson, University of London Press, 1949.

(2) Pages 15-18, 'Calcutta',

Geoffrey Moorhouse, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1971.

(3) Nathaniel, a nephew,

is mentioned in J. C. Marshman. William must therefore have had

at least one brother (see Chapter 24).

(4) Ward was not an

uncommon name in the town. The Derby Local Studies Library has

an alphabetical index of references to local residents found

in Parish Registers, histories, biographies and newspapers etc.

Between 1702 and 1788 there are 15 references to different John

Wards. The closest entries to the relevant time are:

a) the 'apprenticeship

of one John Ward to Edward Fletcher, joiner, on August 16th 1762'.

b) the 'marriage of John

Ward to Ann Fletcher, at St Alkmund's, on September 12th 1764'.

The occupation ties in with

what we know from Stennett. It is quite feasible that John married

his employer's daughter.

It's worth noting that there

were few dissenters at that period in Derby and those churches

that existed were not legally allowed to hold infant baptisms.

Most babies were baptised at their local parish church within

eight days of birth. If the above records refer to William's

parents then the baptism would probably have been at St Alkmunds.

Unfortunately the records of baptisms and deaths at St Alkmund's

do not exist for the period 1729 - 1813. It is therefore not

possible to find records of William's baptism, or John's death

that is if St. Alkmund's was their parish church. Currently,

no reference to the infant baptism of William Ward has been found.

(5) In the records of

Brailsford Parish Church

two interesting entries are recorded: 'Thomas Ward of Stretton

married May Fone on 3rd May, 1720'; also, 'Thomas Ward

of Stretton married Hannah Morley on 18th June, 1728'.

Whether these are both the same Thomas Ward is not known, but

to have the village attached to both names is unusual. To have

two different Thomas Wards in the same small village, both marrying

in the same Derbyshire village, some sixteen miles north of Stretton, is unlikely.

The marriage, by tradition, would have taken place in the parish

of the bride.

(6) In her biography of the energetic Quaker evangelist

Abiah Darby (1716-1793), Rachel Labouchere quotes a letter dated

30th September, 1774, which mentions a visit to Derby on page

173. 'We had many glorious meetings as we passed along, both

among friends and others. We had a meeting at Barnard Castle

in their Town Hall, one at Norton in the meeting yard, one at

Tadcaster in the Methodist House. One at Harrogate in one of

the Rooms and at Derby, Burton and Lichfield in their Town Halls,

and all where no Friends had meeting houses which were

extraordinary opportunities but rather no Friends dwelt

in these places yet we were not destitute of friends' Company

for several met us there, accompanied us to them, and at Derby

we dined four and thirty friends, tho' none lived very near.'

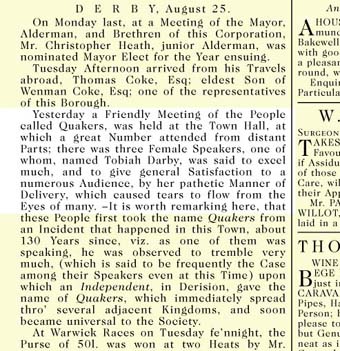

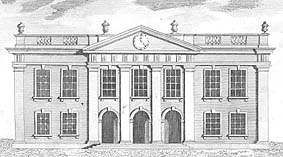

According to the edition of the 'Derby Mercury' quoted above,

this meeting at the Town Hall, Derby, took place on 24th August,

1774. The building had been rebuilt in 1730 to replace the previous

Town Hall, and Abiah Darby may not have known that the meeting

was being held on the exact spot where the founder of the Quakers,

George Fox, was imprisoned between 1650 and 1651. The previous

Town Hall housed the town gaol on the ground floor.

Abiah Darby was the wife of

Abraham Darby II who inherited the ironworks in Coalbrookdale,

Shropshire, from his father, Abraham Darby I. Coalbrookdale was

the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution.

According to a leading member

of today's meeting, Abiah Darby is known to have contributed

financially to the Quakers of Derby.

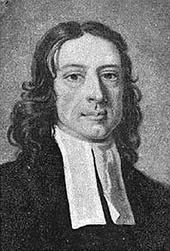

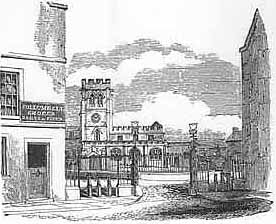

Derby's association with the

Quakers goes back to their founder, George Fox, who was imprisoned

for blasphemy in the notorious town gaol, below the Town Hall,

between 1650 and 1651. At his trial Fox bid Justice Bennett to

'tremble at the word of God'. Bennett scornfully nicknamed him

a 'Quaker', and the name has stuck ever since. The forces of

Cromwell were recruiting in the Market Place and since: a) his

sentence was coming to an end; b) he was regarded as a born leader;

and c) he talked sense about religion, he was brought before

the commissioners and soldiers and offered a commission on the

spot. He refused, and was thrown back into the dungeon, 'a lousy,

stinking low place without any bed', and kept there for six months.

('George Fox and the Valiant 60', Elfrida Vipont). The prison

used to flood when the nearby Markeaton Brook overflowed, which

was not uncommon.

According to Simpsons 'History

and Antiquities of Derby' the Quakers in Derby were one of the

earliest establishments of that body. They survived discreetly

and built their first meeting house in 1808 on St. Helen's Street.

It still survives almost unchanged to this day.

For more information about

Ironbridge, go to the Ironbridge

Gorge Industrial Museum web site

(7) There had been a

Grammar School in Derby since 1555 (created by a Royal charter

from Queen Mary). The school produced some gifted pupils, including

the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamstead. It was available,

free, to the sons of Burgesses and Freemen as part of the school's

Charter. Wealthy parents were willing to pay for their sons to

attend and this raised the standard of teaching. However, by

the end of the 18th century, with public boarding schools coming

into existence (such as Repton), wealthy parents no longer sent

their sons to the Grammar School. This meant a decline in standards.

William was not eligible for the Grammar School, so his widowed

mother must have struggled to provide him with the education

he actually received. There were small private schools in the

area of Green Lane and The Wardwick so William probably went

to one of these. At the Derby Local Studies Library there is

a list of all the pupils who ever attended the Grammar School

when it was at St Peter's Churchyard. There is no record of a

William Ward.

(8) Rough and tumble

did not mean just schoolyard games, but a form of legalised riot

called the Shrovetide Football Match. The game bears no resemblance

to any football match we know. The young men living south of

Markeaton Brook were named after the parish of 'St. Peter's',

and those living north of it were called 'All Saints'. It took

place on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday of each year. Shops

and businesses were boarded up as the whole town was the pitch

including the river and the brook. The ball, a solid mass

of leather, was thrown at noon into the dense mass of people

assembled in the Market Place to a great roar. The crowd heaved

and wrestled the ball either to Nun's Mill, which was the aim

of 'St Peter's', where it had to be struck three times against

the water wheel in order to score a goal, or for 'All Saints'

the goal was Gallows Baulk, on Osmaston Road. Teams of specialists

were positioned at strategic places to attack the opposing side.

The tactics were intrigue, bluff and brute force. The game went

on till night, and was resumed on Ash Wednesday. In 1846 the

game was abolished by the Mayor. ('Some Reminiscences of Old

Derby', Alfred Wallis, 1909, one time editor of the 'Derby Mercury')